Conclusion

Designing for Enthusiasts

With this thesis I have explored how to implement dynamic difficulty in escape rooms. Unfortunately there is no cookie-cutter solution to implement dynamic difficulty (yet). The result of this research project are several recommendations, or levers, that can be considered when developing a dynamic difficulty system for escape rooms.

To conclude, I will summarise my findings and answer my primary research question.

Research Question

How might we offer an escape room that challenges enthusiasts without alienating novices?

Some of the recommendations I make in this conclusion apply to the inputs (metrics) and outputs (resulting adaptation), while I will also provide some that apply on a meta level (goal of the system).

Input

Most escape rooms, and especially the ones doing dynamic difficulty, determine puzzle difficulty by duration. While you might say time is a reliable indicator for performance, this does not directly mean players have an enjoyable experience. Time moderation can do an excellent job at selectively picking which puzzles are skipped when a team is slower instead of cutting off the end. This means it's possible to have players experience the entire story (though less rich), instead of leaving them at a cliffhanger.

Time as a metric doesn't say anything about the perceived difficulty of a puzzle or escape room. It could very well be that a team finishes a game within 36 minutes. However, if those were the best 36 minutes of their life, that could be worth it. The idea that they could have had 60 minutes of that same high-quality experience with a perfectly matched difficulty might start to sound compelling now. I propose escape room designers look at three different metrics other than time to gauge a perfect challenge. These can be combined with time to (theoretically) create a game with perfect difficulty, while simultaneously offering everyone an equal amount of play time.

Engagement & Frustration

Recognize when players are bored or don't know what to do. When they become disengaged, they will sit around, start breaking things and they are usually physically distanced from the puzzle to solve. Frustration is generally recognized by groups making lots of mistakes. Is the group guessing or are they still interested in learning how to solve the puzzle?

Momentum

Consider whether a group is picking up speed. Rather than looking at time, look at the acceleration of their performance. Measure whether they are solving puzzles faster than earlier on in the game.

Team communication

Instead of looking at individuals through physiological data, we might do some analysis on the performance of a team. Sawyer and Marlow have shown teams that know each other well communicate less often, but to more effect. They know who to ask for which type of puzzle.

Output

As for output, several suggestions can be applied to improve escape game difficulty as well. Firstly, it's important to restate that unfair puzzles and unfair escape rooms can't be fixed simply by dialling down difficulty. When you consistently frustrate players with the same puzzle (whatever their skill level), that may be due to the presence of a logical gap. This creates unfair puzzles, and unfair puzzles require specific interventions. For example, if you know something as a designer that players don't, the puzzle won't be solved by reducing the steps to solve, you have to share that information.

When directing players, attempt doing so with gentle nudges first. The output of a dynamic difficulty system should be subtle. Like changing lights to signal important items and directing music to a specific part of the room. When puzzles shouldn't be played, it should not be too obvious they exist only for faster players.

It's impossible to adjust the experience to fit every player in the room individually, especially when there is a large spread of skill levels within the team. Regardless of whether we're able to sense how each individual feels through physiological measurement, it's a complicated endeavour to adjust interactions based on who interacts with them. Which is even more true when players interact with the same puzzle.

As a stretch goal, escape room designers could adapt beyond difficulty. They could adapt gameplay based on specific skills or preferences. For example, familiar teams communicate better. By increasing interdependence for these teams, we ask them to rely more on each other compared to other teams. Opposed to that, unfamiliar teams that have escape game experience individually (a group of enthusiasts meeting each other for the first time) are likely less adept at communicating effectively. These individuals are skilful at escaping, since they have seen lots of escape game puzzles before, and know what to look out for. Instead, we could split them up a little more than usual to work on puzzles individually or in duos.

Difficulty of the unfamiliar, as Nick Moran calls it, is difficult to moderate. The players' ability to overcome obstacles like these is primarily a function of prior experience. By breaking the mould, we can craft obstacles that are relatively hard for an enthusiast, compared to the novice, since everything is new to the latter. Creating unfamiliar puzzles is easier said than done however. Actually, the increasing amount of escape rooms likely means it's harder and harder to come up with interactions that are new to enthusiasts. The result is that it's increasingly difficult to offer novices and enthusiasts the same challenge with a single puzzle variant. Which makes the argument in favour of dynamic difficulty stronger.

Meta-level

Most highly rated games are highly linear. That doesn't mean there is no room for games that offer a challenge, since I did learn some enthusiasts do like solving challenging puzzles. Who enjoy overcoming hard obstacles more than others.

Based on my research and experiences, I think many games can thrive without difficulty, and games do get rated poorly when they are too hard and especially when they're unfair. It's a risky endeavour to make challenging escape rooms, because challenge and fairness are hard to balance. Moreover, challenge-based immersion requires that players get the exact difficulty that matches a team's abilities to get an optimum experience. The required challenge is influenced by their varying abilities, which depends on a group's familiarity too. However, I've also learnt that designers can get away with a lot. Like the skip button in Push the Button. So long as they fit it in the narrative, and players never get the idea that the puzzle or escape room is unfair. These decisions may offer a better experience than not implementing them, even if they would be potentially game-breaking when they don't fit the theme and narrative.

It could be argued that escape rooms are somewhat dynamic already. Games become fair through a robust clueing network, but difficulty can be lowered by correctly timed (and subtle) hints. If you can't be subtle about dynamic difficulty, you could try to make it part of the narrative. Explain why the difficulty is not the same for every group.

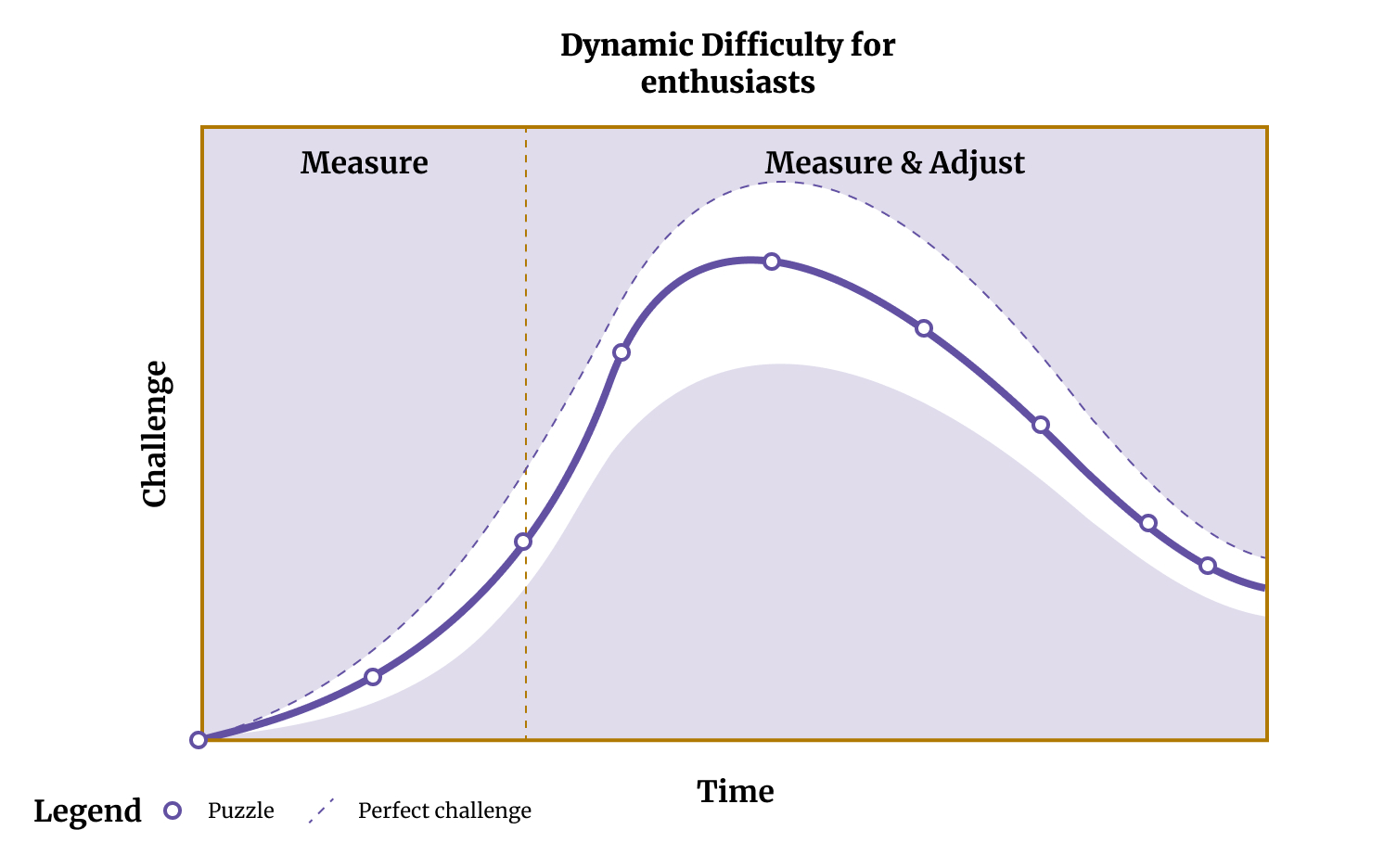

Dynamic difficulty should always start easy, just like a traditional escape game. At the start it's hard to gauge a team's speed, or their wishes for difficulty. And when players disengage early on in a game, it's hard to get them to trust the designer again. Employ a bell curve to scale difficulty, but make its steepness and peak depend on the team's abilities.

Finally, escape game designers aim to create consistent experiences, so players of any level can talk about their experience without major narrative disconnects. Designers want the medium to be as consistent as movies, even if they could be as reactive as video games. Moving forward, escape room designers should embrace the medium for its own strengths. To be as flexible as video games while being more immersive than video games and movies will ever be. Their consistency should be how difficulty is perceived, not how complex they are, or the exact narrative being followed.

These levers are small wins, but combining those can potentially influence the experience with a fine-grained control not previously seen in escape rooms.

Dynamic Difficulty System

I propose a dynamic difficulty system (DDS). I've learned, escape games have to gradually introduce groups to challenge. Every team starts off with the same challenge, this time can be used to assess team performance and enjoyment. The DDS collects data on engagement and team communication as indicators for the desired challenge, and applies momentum later on to self-correct. Simultaneously time should be monitored, to ensure players get an experience that maximises the time spent inside the room.

- To moderate for difficulty, easier and more difficult versions of the same puzzle can be employed.

- To moderate for time, puzzles can be added or omitted.

- Puzzles that are more difficult, likely take more time to complete as well. Game designers should be aware that time is influenced by difficulty tracks as well.

The system should make real-time predictions of the current perceived difficulty and estimated time of completion, always keeping the two in balance. A system like this could provide different types of teams different experiences, regarding time and perceived difficulty.

Many game designers see the need for dynamic difficulty as an issue with the game. They see it as an error in game design when too many teams need a hint. Instead I see that differently, a DDS could take giving hints to the extreme. Like in The Gallery where some groups would actually like to attempt to figure out a mastermind puzzle, while other groups will only want to input simple steps. This idea isn't currently welcomed by everyone in the industry, but I believe this might change when a DDS has been executed well enough that it improves the experience. As such, my final conclusion of this report is as follows:

conclusion

The goal of dynamic difficulty is to moderate the experience based on time as well as perceived difficulty. To keep teams in a flow state while being aware this influences the time it takes groups to escape. The goal is to intellectually and physically challenge the group throughout the experience. And to make teams escape with minutes to spare, during which they perform at the highest of their abilities regardless of their skill level. This positively affects total immersion, as a result of increased challenge-based immersion.

Further research

As recommendations for further research I'd suggest an in-depth look at practical tools for real-time measurement of team performance and group flow.

Another area of interest could be statistical analysis into the psychological need of escaping (as opposed to failing escape). Whether players review games they escape from more favourably than games they do not. Are the games they don't escape from perceived as so difficult they perceived as unfair? Does it matter how much of the game they did play. Concretely, does it matter if around 20% of the experience is left or 60% is left?

Some enthusiasts care about setting records, though many I spoke with do not. Since dynamic difficulty would create unfair records when players do not play the same game, I suggest to research the desire for setting time records. And whether that's more important than playing an escape room that matches their abilities.

My final, most promising and concrete recommendation is to do an analysis of team dynamics applied to escape games. What are the characteristics of fast teams? Team characteristics could regard personality types, group relation (colleagues, family etc.) or communication styles.

Reflective Statement

During this project I became most excited after I had read something or talked to someone. Gaining new knowledge allowed me to make new connections between what I had just learnt, and what knowledge I had recorded before, which was always exciting.

While writing these final weeks, I had trouble fully fleshing out sections of knowledge. I kept jumping around in my files, and left many sentences unfinished because I had just thought of something that just had to go somewhere else. My solution was to tell Francine, who I'd been checking in with frequently, what I'd be writing that day. This acted as a social check. I copied that small section into a different text editor, which means I dedicated myself to that task. Finally, I set a Pomodoro timer, so I reminded myself not to get distracted during that time. This worked very well for me and helped me elaborate on previously surface-level paragraphs of knowledge.

One of the best experiences I've had during my education was hosting the panels with escape room legends. And that says a lot, because Hyper Island has had some incredible industry leaders and guest-speakers as well.

I think much of what I've learnt during this project is applicable throughout the field of experience design. And I have a positive outlook that I'll be able to translate what I've learnt in a different domain, like Nicole Lazarro has done. Transposing her work to the field of user experience design as a whole, as she's demonstrated with her talk at AIGA Conference. I'm excited as much as I'm relieved to finally put this work out into the world.