Literature Review

Theory of Game Design

To effectively design for escape rooms, it's important to know what makes them challenging and fun. This chapter aims to uncover why people like playing escape rooms and what makes a good escape room. We'll dip our toes into each of the defined research questions to get a fundamental understanding of the problem at hand.

What makes or breaks an escape room experience?

As I tried to explain above, there are many types of escape rooms. With different areas of focus regarding the areas they direct the player's attention to. Furthermore, they are built around a variety of themes. What's consistent however, is that players usually have to ‘escape’ a room filled with challenges within a given time limit. In some cases those challenges don't ask much from the players. In some cases they might just ask players to traverse from space to space. Generally however, escape rooms have puzzles at the heart of the experience. Which is the first part of escape rooms we'll look into.

Puzzles

The anatomy of a (good) puzzle is complex. If puzzles would all follow the same basic formula, they likely wouldn't be a puzzle anymore, since that would make them predictable. Puzzles can take various forms and styles, to be decided on by the designer. Though there are also factors every puzzle is made up of. The following theory applies to 'escape room'-style puzzles only, and may not be applicable to other types of puzzles (eg. sudoku's, jigsaw puzzles and crossword puzzles).

Wiemker, Elumir & Clare (2015) define that at the heart of every puzzle is a:

- Challenge — a locked box

- Solution — a combination

- Reward — the contents of the box

This is a repeating pattern, a (potentially infinite) loop of challenges. Each reward holds the key to the next challenge (Wiemker, Elumir and Clare, 2015).

Designing Puzzles

Bob Bates (1997) suggests puzzles have been at the heart of (adventure) games since the beginning. Stories and characters were rarely seen in video games, with his essay Desigigning the Puzzle, Bates signalled that was no longer true. It argues good puzzles contribute to plot, character and story development. While these characteristics say nothing about the interaction on its own, they are crucial to nail the experience as a whole. Because the puzzles that do this well, draw the player into the fictional world, make them care about solving the puzzle. He is adamant about the requirement that puzzles are fair and make sense. Good puzzles exist to be fun, rather than to prevent players from finishing. Contrarily, bad puzzles are intrusive and obstructionist. Puzzles designed like that frustrate players and players perceive them as a device to make the designer look smart.

Fair Puzzles

Escape room designers should pay extra attention to create fair and enjoyable puzzles. Errol Elumir articulates several points in favour of this. He says, that as escape room designers we should have the ambition to make puzzles that are to be solved with only the information in that room (2018). He doesn't see players as adversaries, and as a designer, he's on their side. We should not trick people, we should not mislead them. Designing puzzles is not about putting in roadblocks to ensure a humbling defeat. Ultimately, designers shouldn't set out to prove they are smarter than the player. He writes:

As a designer, I want people to solve my puzzles. I take no delight in people’s failure

- Errol Elumir (2018)

Elumir explains that this does not mean all puzzles have to be easy to solve. A puzzle can be difficult and enjoyable at the same time. Players will embrace difficulty, and don’t mind failing so long as failure feels fair to them. When playing escape rooms, players expect to rely solely on their wits and each other. When this expectation isn't granted, bad puzzles (and bad escape rooms) are the result. Bates writes a common player response in a situation like that is: “There is no way I could ever have solved that. I don’t even understand it now!”. Even 20 years later, a common error is that players have to guess what the designer thought while creating a puzzle, Elumir notes.

Puzzle difficulty

It should be obvious that designing extremely hard puzzles shouldn't be the primary goal. However, when we do want to increase or decrease difficulty to cater to different players, there are several (metaphorical) dials to turn. Bates argues designing difficulty is actually one of the easiest parts of puzzle design (Bates, 1997). He suggests several ways to make puzzles more or less difficult:

- Breadcrumbs — Change the amount or directness of information to players

- Alternate solutions — Adding alternate solutions make a puzzle easier

- Proximity — The closer the solution, the easier. This can be split up in two ways:

- Psychological — The amount of logic jumps to make required to solve the puzzle

- Geographical — The physical distance to a solution

- Steering the Player — nudging in the right direction, as a response to player actions

While this isn't exactly an extensive list, it's important to consider that they offer very broad advice. The effect these adaptations have on a puzzle are dependent on the puzzle type, the context they are in and what type of player is solving them.

Bates closes his essay with the argument that puzzle designers should develop player empathy, the ability to put themselves into the player's shoes. Bates establishes that this is a key skill to determine whether a puzzle is "fair and reasonable". It allows us to consider what situation a player is in, whether they know what they should solve, and what the blocking obstacles are to resolve. While Bates does emphasise the importance of empathy this is also where this article starts to show its age. As a user experience designer, actually testing a proposed design solution is at the core of my work. What Bates does with 'player empathy' is now a much more profound part of the process of puzzle design. Game designers nowadays objectively test their games. Instead of trying to guess what player will feel while playing, they observe players to find problems in their designs.

Balancing difficulty

Rita Orlov (2018) describes how puzzle difficulty is a balancing act. She says, regardless of the targeted difficulty level of an experience, it's important to be aware why players are unable to solve a puzzle. Whether they fail because something is confusing or obtuse, instead of their inability to make a logic leap.

We gain that ability best through rigorous testing, by which we're able to continuously shave on the experience. In escape room design this can be done through several ways, Rita Orlov (2020) explains she tests several factors. Puzzles may break in several ways, including whether clueing is direct enough, if it's possible to solve with the information players have and because of issues in the physical context it is set in. Testing all these factors with real players and understanding what happened makes the game more fun.

The Compulsion Loop

As I alluded to before, puzzles aren't self-contained interactions. They are part of the entire escape room 'system'. Escape rooms host a repeating pattern of varying interactions, that connect through their input and output. Nick Moran describes in his talk Tools of Immersion, how to ensure players know what to do, by successfully implementing the compulsion loop (Moran, 2017).

- Desire — each puzzle starts with a desire. The need to go somewhere, or get something.

- Obstacle — this desire is blocked by a certain obstacle. The puzzle is removing that obstacle.

- Reward — upon unblocking the obstacle, players receive a reward. Which should point towards the next desire.

- Repeat — by repeating this loop, players know what to do next.

Repeating this loop leads players from one challenge to the next, and each reward shows players what desire to care about next. When this isn't clear, people are lost and they lose interest. Clearly, maintaining the compulsion loop is essential to ensure players enjoy the escape room as a whole.

Puzzle paths

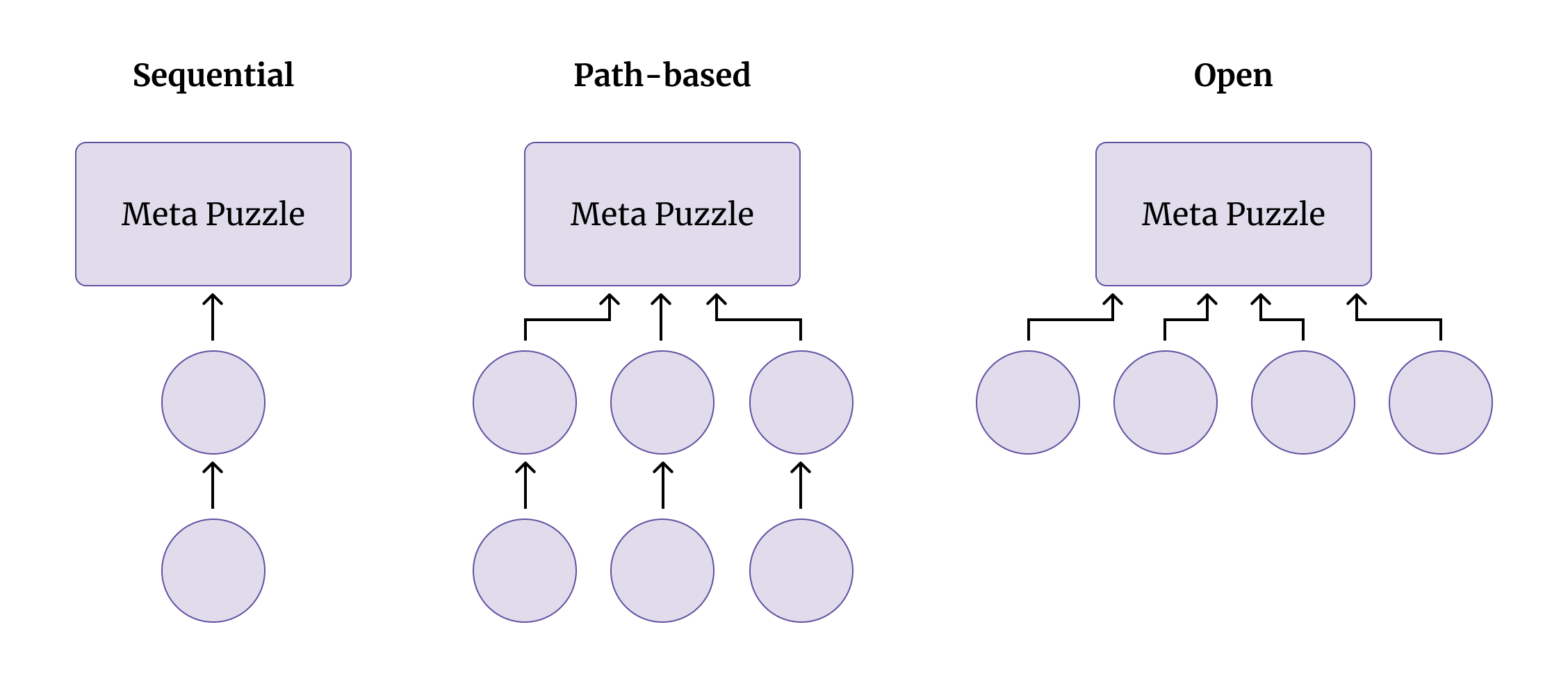

This is obviously a simplified way of looking at things. The distribution and placement of puzzles plays an important role in any escape room. The gameplay loop is rarely entirely linear, and in most cases might even seem chaotic. The approaches most commonly seen incorporate the compulsion loop in some way. Heikkinen & Shumeyko (2016) identify three:

- Sequential — this is a mostly (or entirely) linear experience. Each puzzle only leads into a single new puzzle.

- Pros: Easiest to follow (strong effect of compulsion loop). Most control over progression of difficulty.

- Cons: allows for no parallelisation. The team has to work on each challenge as a whole, whether they're with two or 8. Quickly becomes tedious or boring.

- Path based — multiple paths of puzzles are available at the same time. These paths often lead to a single, final puzzle. The meta puzzle.

- Pros: Allows team-work and parallelisation, allowing for bigger groups to play the escape room. When the meta-puzzle clearly shows what paths have not been completed, players still know what to do next.

- Cons: Easily distracts and confuses players.

- Open — all puzzles are separate, and stand on their own to escape the room.

- Pros: Allows for lots of parallel puzzle solving. Everyone is able to work on something individually.

- Cons: Individual experience. Confuses players (no compulsion loop to motivate next moves). Hard to control progression of difficulty.

Immersion

As Rachel Sugar (2019) explains, one goal of Escape Rooms is to immerse the player in a story, set in another world. They make you temporarily forget about work, your phone, and everything else going on in life. Escape rooms' promise is a temporary escape from reality. Highly immersive experiences are about creating a world that never ends. This brings out the maximum emotional response in players (Moran, 2017).

This is also an obvious business goal, as people who are immersed in media also tend to enjoy it more (Madigan, 2010). Which they will share with friends, family and strangers through word of mouth.

Types of immersion

To achieve an escape from reality, and become immersed in a fictitious world, we should understand what that actually means. Unfortunately, the definition of immersion isn't clearly established, and the true cause of immersion is still something we can't quite put our finger on.

Clear and testable definitions of constructs such as immersion and flow would be invaluable.

- Nacke & Lindley (2008)

A variety of explanations, overlapping theories and opinions are discussed within the realm of the psychology of games. The term total immersion is often interchangeably used with the concept of spatial presence; a state wherein we are wholly consumed by feelings of empathy and atmosphere. Lennart Nacke and Craig Lindley explain how Ermi and Mäyrä have categorised the types of immersion typically found in video games (Nacke and Lindley, 2008).

- Sensory — audiovisual execution

- Imaginative — absorption in the narrative

- Challenge-Based — emergent gameplay experience

While this might not be a conclusive list, Ermi and Mäyrä cover a range of qualities that cause immersion. At Up the Game 2018, Liz Cable (2018) speaks about physical, emotional and intellectual immersion. Her descriptions of these types of immersion relate closely to sensory, imaginative and challenge-based immersion respectively. Indeed, these theoretical factors seem to translate well to the physical spaces of Escape Rooms as well. In the next section, we'll discuss how escape rooms attempt to fulfil these qualities. We'll also go over which areas escape rooms excel at, and where they lack compared to other mediums.

Sensory

The audiovisual execution of escape rooms have improved enormously since its earlier days. Sensory immersion is the result of effectively stimulating as many of our senses as possible. Considering primarily what we feel, see and hear, though some escape rooms have started targeting what we smell and taste as well.

Spatial Situation Model

We find a scientific explanation for strong sensory immersion in escape rooms through the spatial situation model. From the perspective of video games, Wirth et al. (2007) explain the formation of spatial presence (aka total immersion) as a two-step mental process. Simply put:

- The mind starts to establish a mental representation of the space or world that is portrayed, and what kind of place it is.

- Slowly it starts to prefer the new space as its point of reference. It establishes whether it, the mind itself, is located within said place. The primary ego reference frame changes.

They define that the spatial situation model (SSM) is a precondition to the occurrence of spatial presence.

Video games need to be rich experiences and require attention from the player, for them to construct a mental representation of an imaginary world. If any of these conditions is not met, total immersion can not occur. When players truly believe they are within a new environment entirely, they are able to form spatial presence. To be in total immersion of this world.

Escape rooms have nowhere near the competition for attention that video games do. We control our own body, and are actually in another environment. With no secondary environment to distract us, we can forgo many of the processes necessary to form spatial presence in a virtual environment.

Imaginative

Imaginative immersion considers the narrative component of an experience. The importance of narrative in escape rooms has been an ongoing discussion. Some players are perfectly fine with a thin narrative, whereas primarily come to an escape room to explore an interesting story. Narrative doesn't only consider the story, but several other factors to consider as well (Nicholson, 2016):

- Story — the spoken or written part of the story

- Space — the environment telling part of the story

- Puzzles — progressing the story by interacting with it

It's easy to see how escape rooms are immediately more immersive than video games, due to players actually being in a room, instead of controlling a virtual character. Compared to immersive theatre however, they lose out on imaginative immersion.

Haley ER Cooper is one of the co-founders of Strangebird Immersive, an immersive theatre company (theatre plays that the audience participates in). Their first experience actually also happens to be an escape room. With a focus on immersion, Cooper might be the best person to learn from when it comes to making immersive escape games. She writes an immersive theatre escape room is hard to achieve. The primary requirements of immersive theatre (immersion through storytelling) conflicts with the mechanics of escape games.

She argues that, while escape rooms certainly physically encompass the players, escape rooms should do more world building than most do.

Most escape rooms feel like spaces designed for a game more than inhabited places. They often look a little empty. And there are good reasons for that…

- Haley Cooper (2017)

The big difference between real spaces people actually live in, and an escape room is the latter tends to feel like an empty husk. As a result, escape rooms have more in common with something you would see in the photos of an architecture portfolio, than the workspace of someone like Nikola Tesla. Each object in an escape room has its purpose, and is heavily curated. It has to have a purpose within the world, setting and genre expectations (Nicholson, 2016).

Clearly, escape rooms offer a limited amount of interactable objects for a reason. If the escape room would be like a workshop, a significant portion of the allotted time would be spent on identifying the puzzles, instead of solving them. While the modern interior certainly has a less interesting story to tell, it would make for a better escape room environment. Of course these are extreme examples, but they illustrate Cooper's point well. The mechanics of an escape game directly contradict those of narratively immersive experiences.

Challenge-based

Fortunately, escape rooms excel at one thing; offering challenging puzzles to draw the player in. They make the player an active component in their own experience, unlike watching a movie at the cinema, for example. While a great story adds to a great experience, even escape rooms with poor narrative execution get people drawn in. Escape rooms, good or bad, put the player front-and-center by definition. They have players exploring, observing and actively participate in the scene (Cooper, 2017).

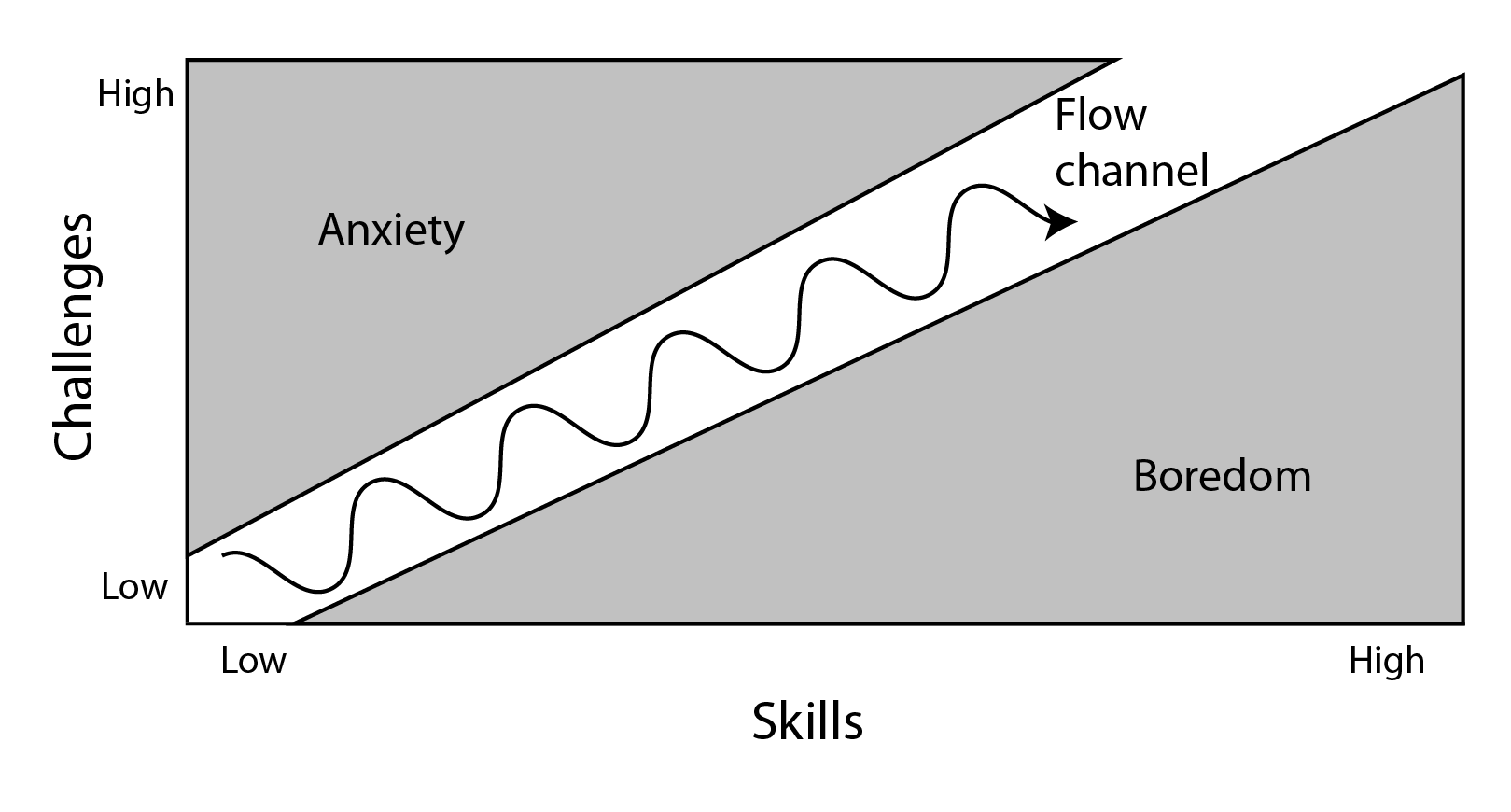

Flow

We can't talk about challenge-based immersion without discussing the theory of flow, a well established concept in psychology. Introduced by Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi (2008), flow is defined as an optimal experience; a challenging activity that requires skill. One in which we perform at our highest abilities. Activities that put us in a state of flow are goal-directed and bounded by rules. Meaning we know what to do, and how to get there. When a state of flow is reached, it completely consumes what we're doing and makes time pass without us noticing. Csikszentmihalyi (2005) determined flow occurs in an individual when a set of specific conditions are met:

- Clear goals and immediate feedback — goals keep us focused on a task. Immediate feedback on progress towards upcoming goals keeps us motivated and allow for more efficient determination of next steps

- Continuously challenging — engaging in challenges that are appropriate to our abilities we think we can achieve.

Human beings love a challenge. In the context of escape rooms, well-designed puzzles and game flow are a prerequisite to high levels of immersion.

Keeping players in flow is a delicate balance. Players start a game at different levels of skill, their skill level changes through time and it's hard to know whether they are currently experiencing flow in the first place. Game designers try to achieve this by continuously balancing challenge and cooldown periods. This creates an almost rhythmic movement of experience (Schell, 2019).

The cycle of tense and release, tense and release seems to be inherent to human enjoyment

- Jesse Schell (2019)

Attention span

That cycle of tension and release is something Tommy Honton (2020) talks about in an interview with Constructed Adventures as well. Honton suggests feature films and tv shows have nailed how to keep people's attention. This is because viewers don't have agency over these mediums, directors have complete control over the speed a story unravels at. They're able to control the pacing of emotional low and high points to the second.

Unlike movies, escape rooms give players a lot of control over the way they play, and as a result game designers don't enjoy the same strict control over pacing other tv and movies do. He remarks this is important, since people have a limited attention span. When players take longer than that to solve a puzzle they need a break. If they don't get that, their optimal experience fades.

You can get people to focus for 5-6 minutes max before they need a break mentally. If they solve it [a puzzle], you buy back a little bit of time because of dopamine.

- Tommy Honton (2020)

To restate, flow is reached when we perform at our highest abilities. However, those highest abilities differ from person to person, change over time and everyone does so at a different speed. That's why creating a system that can moderate difficulty based on the ability of players is so important. When we're able to match their highest ability they will experience flow and become more immersed in the experience as a whole.

Recognising flow

It is hard to measure flow, since the act of asking a person whether they are experiencing it, immediately takes them out of that experience (Emerson, 1998). When we discover a method to measure flow, we can use that to determine the optimal challenge an individual or team requires. Csikszentmihalyi does describe what people who experience flow say they felt like during that experience:

- Complete concentration — focused on the present moment, unaware of factors beyond the current context

- Activity becomes spontaneous — action and awareness merge, people know exactly what to do while recognising the next goal

- Loss of self-consciousness — people experiencing flow become unaware of their self, they stop self-criticising

- Sense of control — feeling capable to deal with the situation they are in, the feeling to know how to respond to what comes next

- Distorted view of time — typically experiencing a loss of time, like it's passing faster than normal

- The task is the reward — the activity is intrinsically rewarding, sometimes so much that the end goal is nothing more than an excuse to be able to do the act itself

Schell also describes some indicators of flow in the context of video games. He says while playing solo games, players are often quiet, sometimes muttering to themselves. Interestingly, during multiplayer games, players will often communicate with each other in excitement. Though in both situations they are constantly focused solely on the game.

Purely from a theoretical point of view, narrative immersion and escape rooms don't get along. However, it is clear that narrative immersion is as important to escape rooms as the challenge they present. The main benefit of merging those two worlds would be to allow them both to occur at the same time. For that reason it is important to investigate how escape games can offer clear (proximal) goals, while delivering a compelling story.

Cohesion

Scott Nicholson, a Professor of Game Design and Development at Wilfrid Laurier University wrote a paper called "Ask Why" (2016). With it he attempts to resolve this immersion conflict. He says a similar debate occurred in the video game industry. The debate was driven by two opposing views:

- Narratologists — argued that a games' primary focus is storytelling

- Ludologists — view games as a set of mechanisms that invite play

This debate has resided and efforts have focused on better integration of the two. As a framework to resolve these issues, Nicholson (2016) cites the concept of Narrative Architecture, which is commonly used by the theme park industry to create immersive experiences. Its goal is to embed game mechanisms (challenges, puzzles, etc.) in a larger world. Instead of using the narrative as a shiny coat of paint, it should be woven into the game mechanics and spaces players explore. The narrative progresses as players clear challenges. Puzzles act as gates to unlock the story. Simultaneously they are the touch points with the story. When players are required to understand the story to solve puzzles, it sticks best in their mind.

We've already established this isn't an easy problem to resolve due to the nature of escape rooms. However, Nicholson provides a strategy to achieve a consistent narrative architecture. He writes escape room designers should 'ask why' continuously as they design an experience. He argues each puzzle, task or item should be there for a reason, and that it should be consistent with everything within the room.

Interconnected

Immersion is a complex quality to discuss, as the three types of immersion are highly interconnected. In some ways they strengthen each other, but simultaneously oppose each other in other ways. It's impossible to discuss immersion in a vacuum, and the best way to look at it is as an umbrella term for everything an escape room has to do well. The puzzles, theme, location, story and almost everything else escape rooms have to offer share a piece of the immersion pie. If you look at it like that, one could argue immersion is the most important quality of escape rooms, its raison d’être.

How does the experience of enthusiasts differ from other players?

With the previous knowledge ready, we can start to understand why people enjoy playing escape rooms. What causes people to want to experience them and how does that change for escape room enthusiasts?

Motivation to play

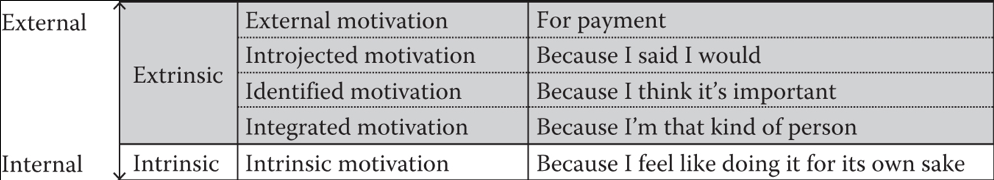

Escape room experiences are appealing through intrinsic motivation, which means we are motivated to play them because we find it enjoyable. On the opposite, extrinsic motivation means we are motivated by an external incentive (like a reward) (Game Makers' Toolkit, 2020).

People's enjoyment of escape rooms might be (partially) explained by the fact that flow is autotelic. Meaning it's enjoyable doing for it's own sake. Activities that cause flow are self-rewarding and pleasurable to do, because feeling flow cultivates intrinsic motivation (Kapitein, 2020). It enables personal growth by being constantly challenging. Flow occurs when the conditions are such that they make us think "I never thought I could do that".

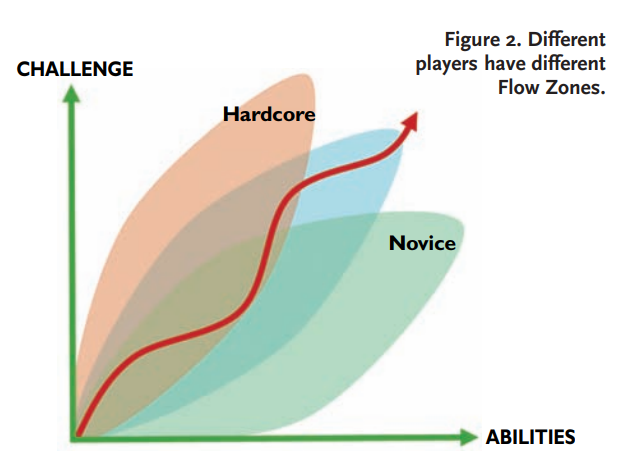

Personal Flow Zones

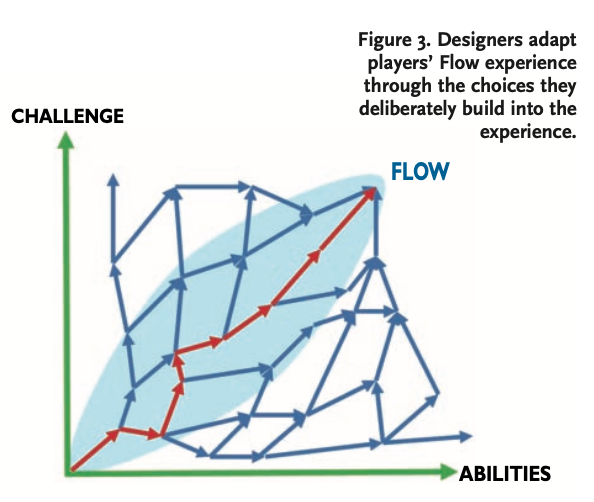

The first hints at the heart of our problem come courtesy of an article by Jenova Chen (2007), which describes Personal Flow Zones. It suggests that not every person starts developing a skill (such as escaping rooms) with the same abilities. And certainly not every person develops those skills at the same rate. Chen describes how designers generally adapt the experiences by deliberately building choice into them. You can imagine this is especially true when some escape room players have already played hundreds of games, and others have played none. Novices will desire less challenge than enthusiasts.

If current escape rooms challenge novices, they might not fit the desires of an enthusiast. When an experience doesn't fit within an individual's flow zone, one factor (challenge-based) of total immersion diminishes. Moreover, in that situation flow doesn't occur either. The result might very well be the loss of the characteristics required to foster intrinsic motivation.

The overjustification effect

Mark Brown, of Game Maker's Toolkit, motivates why it's important to know what motivates us to play a game. His main argument is the consequences of the overjustification effect. Which demonstrates that the presence of a reward makes intrinsically motivating activities less interesting. We become less interested in the task after receiving a reward (2020).

Brown says a few side-effects of the overjustification effect are decreased creativity, decreased problem solving performance, proneness to cheating and losing motivation entirely after receiving a reward.

Mark Brown does have a fairly black-and-white perspective on this issue. Contrarily, Jesse Schell discusses several theories that show how the lines between extrinsic and intrinsic motivation blur when applied to the context of gaming (2019).

Savvy designers know that one motivation can grow on another, like a vine growing on a trellis

- Jesse Schell (2019)

He views the complexity of intrinsic and extrinsic as a continuous gradient, something that is far less binary than Mark Brown sees it. With more nuance, he reasons that all activities start as intrinsically motivated, external rewards can gradually make that intrinsic motivation crumble away.

Considering how rewards influence the player is especially difficult for escape rooms. The key difference in this case, is its fixed time limit. On one hand, we don't want players to rush through the game, only motivated by the promise of escape. On the other, we don't want them to feel lost during their play. It's important that players never feel like they have to rush, while creating clear enough goals for the team to work towards.

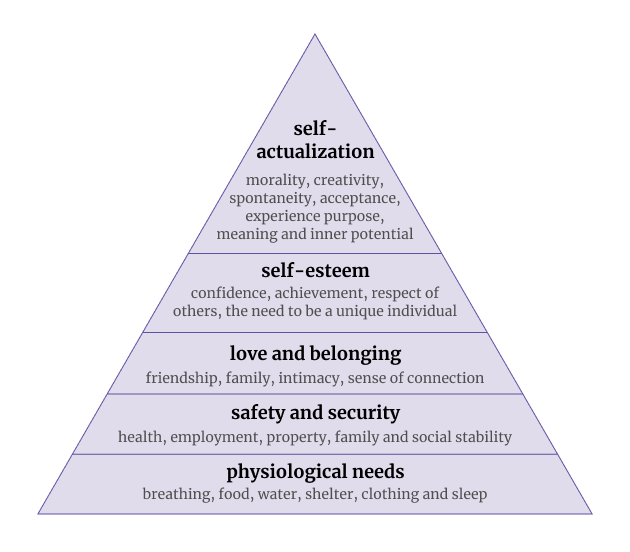

Fulfilling needs

Why even play escape rooms in the first place? In The Art of Game Design, Schell (Schell, 2019) outlines how human motivation applies to game design. Maslow's A Theory of Human Motivation provides an interesting lens to analyse the different activities that games offer. Schell notes that the popularity of games with online communities makes a lot of sense according to Maslow's theories. Maslow's pyramid assumes lower level needs have to be fulfilled before people care about higher needs.

When people's physiological needs are satisfied, and they feel safe and secure, they start to care about the higher levels. Which relate to self-determination theory as well.

Self-determination theory

Beyond physical needs, humans have mental needs as well. Self-determination theory views people as active contributors of their behaviour. They are the "authors" of their own story. Self-determination explains the need for a sense of personal empowerment, involving both knowing and having what it takes to achieve goals. According to Deci and Ryan (2010) self-determination assumes humans have three basic psychological needs:

- Relatedness — I need to connect with other people.

- Competence — I need to feel good at something.

- Autonomy — I need freedom to do things my own way.

Schell (2019) states it's hard to overlook how well games tend to fulfil all three of these needs. Escape rooms (like multiplayer games) provide a sense of connection, through a shared interest and participating in the same activity. Players feel competent by achieving escape, or at the very least they will solve some of the puzzles in an escape room. Finally they can feel autonomous, they can approach problems as a team, and solve them at their own speed. Good escape rooms have to fulfil these needs. Though enthusiasts likely require different challenges to do so. When the challenge proposed doesn't meet their abilities, they won't feel a sense of overcoming. The next section explores how we might alter escape games for these players.

How might we alter escape games based on players?

Previously, we examined the parts every escape room has to do well. And we have established a theoretical understanding of the way players think. A big hurdle to overcome is that we have to understand how players feel during their escape. This should tell us what experience players desire, and how we should tailor the experience to them.

Measuring the Player's Gameplay Experience

There have been several attempts at online measurement of a players' gameplay experience. Online measurement, in this case, means we measure while they play in real-time.

Physiological measurement

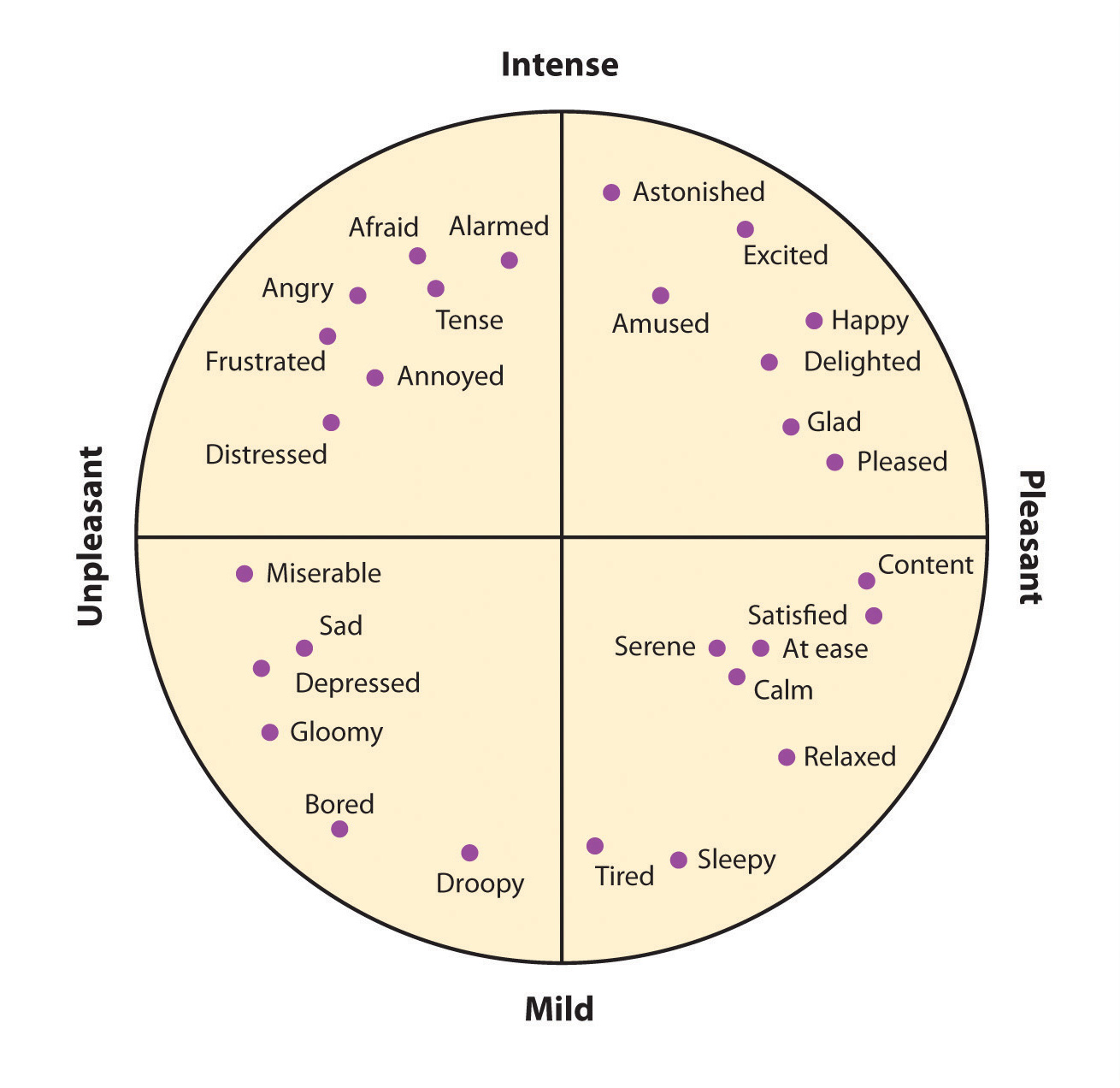

One of such attempts to measure immersion and flow is done by Nacke & Lindley (2008). They measure the emotional state of their test subjects, while playing modified levels of Half-Life 2 (a first-person shooter). They grade the experience on two motivational axes.

- Electromyography (EMG) — to determine hedonic valence, a strong indicator of the pleasantness of an experience.

- Galvanic Skin Response (GVR) — commonly used as an indicator for arousal, how intense an experience is.

Their study suggests that game levels scoring high on flow, show increased values for valence as well as arousal. Using Lang's (1995) dimensional theory of emotion they provide an indication of their emotional state.

If we could reliably use these two measurements to determine emotion, we could control difficulty and direct emotion with incredible precision. Unfortunately it doesn't seem to be so easy.

What is Emotion?

To understand how people feel emotions, it's key to understand what emotion is. Unfortunately, the scientific community has not seen eye-to-eye in this regard. Generally speaking there are three major lines of thinking; Basic Emotional Theory, Appraisal Theory and the Theory of Constructed Emotion. The last one of those is a fairly recent development and redefines how the world currently thinks about emotion.

- Basic Emotion Theory — a minimal amount of emotions are identified.

- Appraisal Theory — defines that emotions are the result of evaluating an event, instead of the occurrence of the event itself (Lang's dimensional theory of emotion builds on this theory).

- Theory of Constructed Emotion — views emotion as an interpretation of physiological changes as opposed to a change in the external environment.

Constructed emotion directly opposes the other two theories, and paints the most conservative picture of determining emotion from physiological data.

Variability

Lisa Feldman Barrett has spearheaded the research of constructed emotion, she shows both physiological changes in our bodies and facial expressions aren't a reliable way to estimate how people feel. Barrett explains how emotions do not cause physiological changes in our body, emotions are in fact the result of the physiological changes in our body. Emotion is how our brains makes these changes feel important to us (Feldman Barrett, 2020).

Your emotions are not your reactions to the world. They are your constructions or more precisely, what your bodily sensations mean in a specific context or situation that you are in.

- Lisa Feldman Barrett (2020)

It turns out that the western idea of universal expressions of emotion are not so universal after all. While some people certainly scowl when they are angry, not everyone does. At the same time, many people who scowl are not angry.

People move their face in very different ways during instances of the same emotion category. They also move their faces in exactly the same way in instances of different emotion categories.

- Lisa Feldman Barrett (2020)

Assuming we display emotion using universal facial expressions suffers from the same problems as assuming everyone entering an escape room has the same level of experience. This mode of thinking only takes into account a small portion of people.

To make matters worse, physiological measurements suffer from a similar problem. When an increased heart rate feels like anxiety, that is because your brains categorizes it as such. The brain fabricates a concept that fits with the physiological changes in your body. As a result, it's incredibly hard to 'measure emotion'. Emotions are dependent of context, and part of that context is the body we take into the room. The formation of emotion changes from person to person, even if we experience the same changes in our body.

Since escape rooms are (generally) multi-user experiences, it makes sense to divert our efforts to examine the escape team as a whole. How do they communicate? What do they talk about, and what don't they talk about?

Team Performance

Marlow et al. (2018) conducted a meta-analysis of team communication. Their research makes three main arguments regarding group familiarity, how well the group members know each other:

- Unfamiliar Groups — frequency of communication is low, and communication effectiveness is low. These groups repeat common information often. Results in low group performance.

- Semi-familiar Groups — communication frequency is increased, but inefficient. These groups share common information infrequently. Group performance is average.

- Familiar Groups — communicatie frequentie is much lower, but more efficient. These groups rarely share common information. Group performance is high.

They argue that familiar teams share fewer redundant information pieces, benefiting communication efficiency. Furthermore, they determined good communication is more important to familiar teams than non-familiar teams.

As team familiarity increases, team members become more adept at locating expertise among team members, reducing the frequency by which team members communicate and increasing efficiency

- Marlow et al. (2018)

This meta-analysis suggests that information elaboration and knowledge sharing have a stronger relationship with team performance than objective information frequency does. In the context of escape rooms this could mean:

- Information elaboration — sharing how an individual thinks a puzzle works

- Knowledge sharing — sharing clues or objects (keys, locks etc.)

- Objective information frequency — amount of times people communicate in total

Group Flow

Like Csikszentmihalyi, Sawyer studied the concept of flow. However, he focused how this applies to groups (Sawyer, 2008). He outlines the ideal conditions for group flow to emerge as:

- Group goals — the group have a common goal, and know what to do to achieve it.

- Close listening — individuals listen to each other, and respond naturally.

- Complete concentration — individuals don't think about anything that's happening outside the current context.

- Being in control — the group feels like they have the capabilities to achieve the goal they are after.

- Blending egos — individuals don't care about who solved something, they take ownership as a group.

- Equal participation — everybody is participating, and nobody gets talked over.

- Knowing team mates — the individuals within the group know each other well.

- Good communication — the group communicates effectively.

- Being progress-oriented — the group keeps moving forward, even if it feels like they're going in the wrong direction.

People experience flow most commonly when in conversation with others, Csikszentmihalyi found. When this occurs, statements are genuine, and unplanned responses to what we hear. Consequently, we may use this to analyse whether a group is experiencing flow.

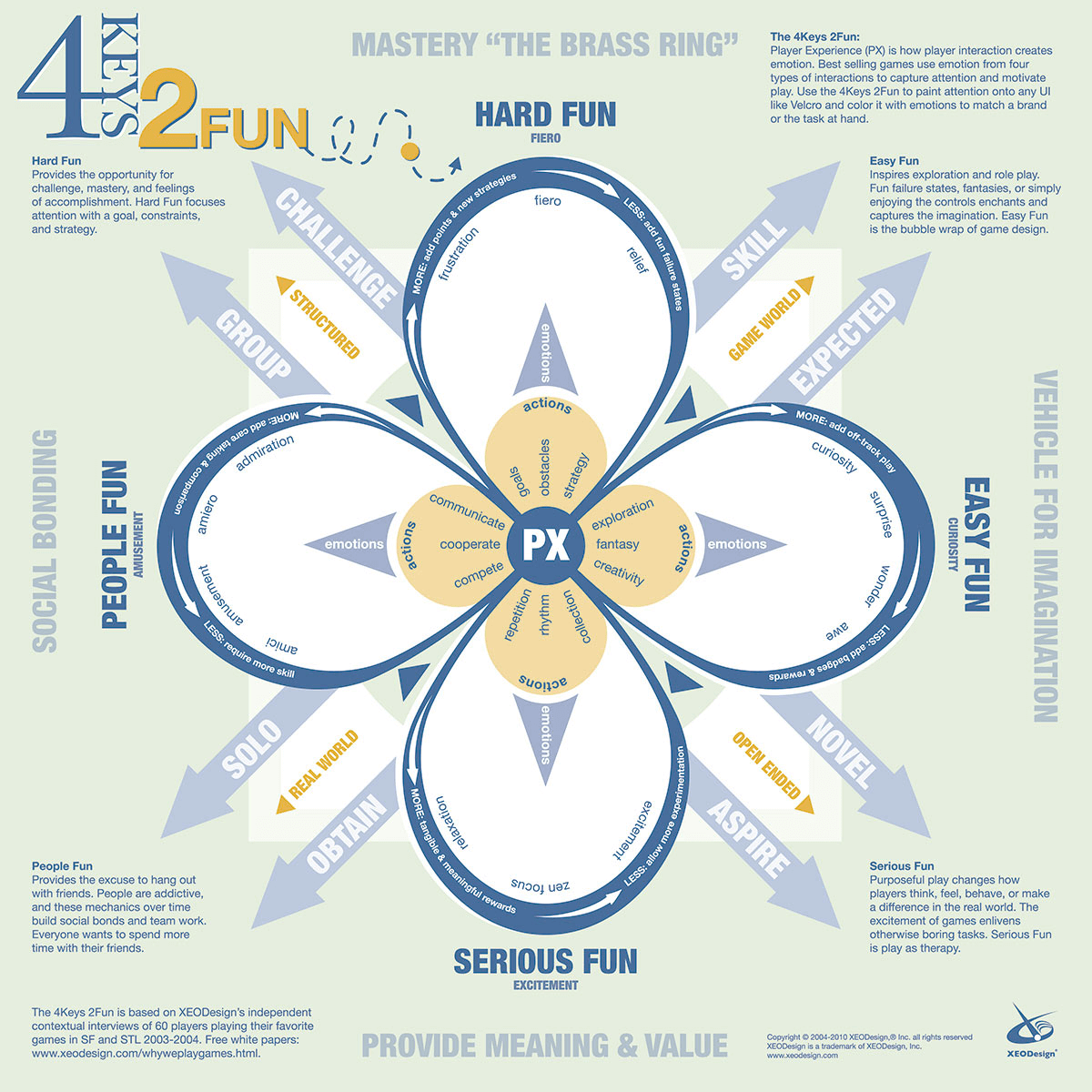

Four Keys to Fun

Nicole Lazarro (2004) has studied players' emotions before, during and after play. Through facial gestures, body language and verbal comments they identified four keys to create emotion without story cutscenes.

- Hard Fun — The enjoyment of challenge and progress

- Easy Fun — The enjoyment of being immersed in a game

- Altered States — The enjoyment of changes in internal state

- People Factor — The enjoyment of playing with others

Players in groups emote more frequently and with more intensity than those who play on their own

- Nicole Lazarro (2016)

Interestingly, the 2004 study doesn't describe any reactive system. I expect this is due to its age, and Lazarro seems to have aimed her sights on it more recently. In her talk Four Keys to Fun: Using Emotions to Create Engaging Design at AIGA Design (2016), she describes how game design and human-centered design relate. She explains how we as designers can react to people's emotions. She suggests systems like those can determine how people feel, and what how tools could respond to these emotions.