Findings

State of Escape Rooms

Beyond what the literature says, there is a plethora of knowledge in the practice of escape room design, that's uncommon in theoretical analyses. Since escape room design is such a young industry, there are relatively few established rules. And the ones that do exist get experimented with or broken entirely, sometimes leading to a better experience. In this chapter, we'll learn how the real world differs from what the literature says.

What makes or breaks an escape room experience?

Previously, we established a theoretical understanding of the inner workings of escape rooms. In practice a lot of nuancing needs to be done to fully understand what makes them tick. Fortunately, there has been extensive — though mostly unscientific — market research on player preferences. We can quickly retrieve some insights from escape room players by relying on the numerous surveys being done throughout the industry. The annual Escape Room Enthusiast Survey is specifically interesting, as it aggregates data from 3000 (self-proclaimed) enthusiasts (Elumir, 2019a).

Elements of an Escape Room

What draws people to escape rooms differs from group to group, and from person to person. The survey ranks the importance of several elements within escape rooms. In 2019, the factors enthusiasts considered most important are:

- Well designed puzzles and game flow

- Novelty & Uniqueness

- Immersion

This isn't a comprehensive list of everything an escape room has to do well. It does however provide us with a handhold to discuss the most important topics. We'll dig deep into each of these factors, and explain them through previously mentioned game theory.

Puzzle flow in practice

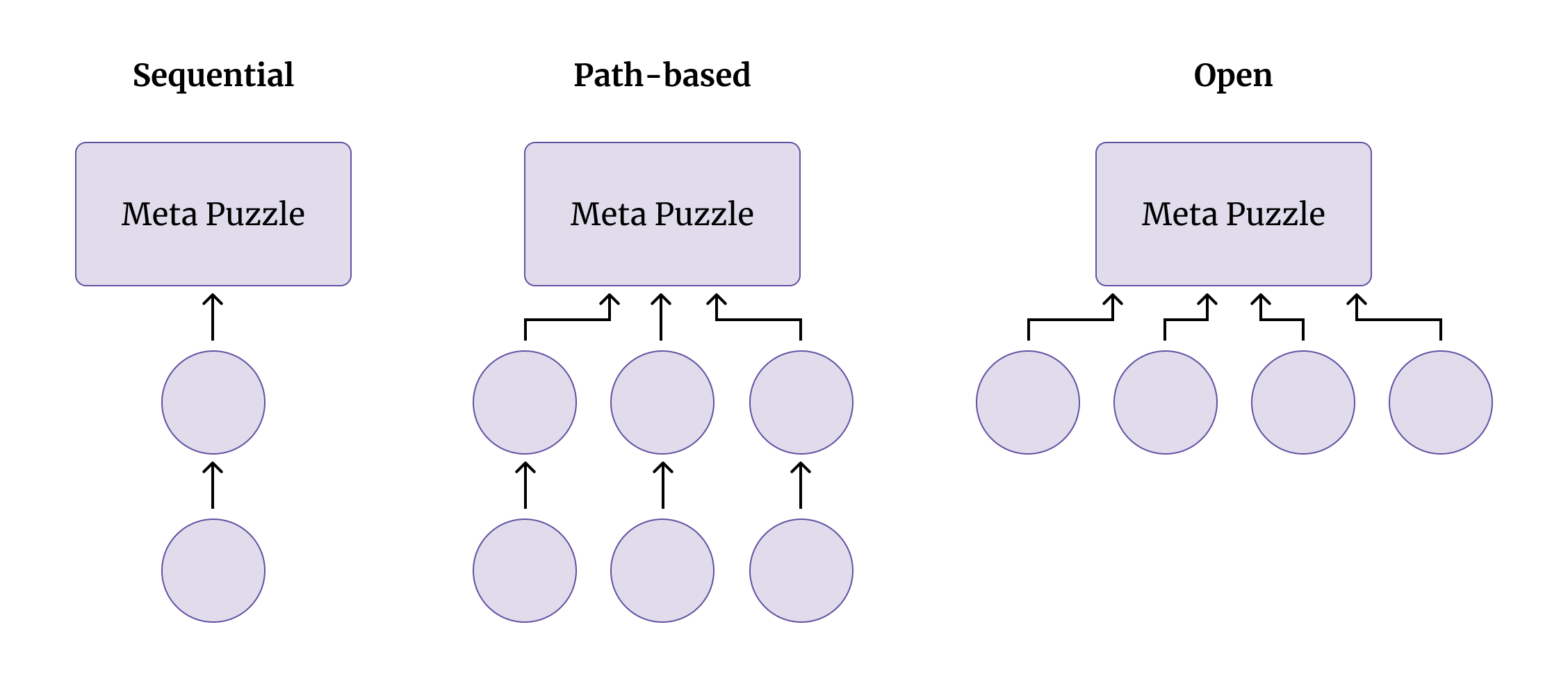

The three models of puzzle flow Heikkinen & Shumeyko (2016) describe, do not portray a complete picture of reality. Real-world escape rooms often combine some or all of these approaches to complete an experience.

In reality, designers might gradually expose more and more rooms within the room. Or they might choose to direct players to work together, so they don't miss the most important story points of the experience.

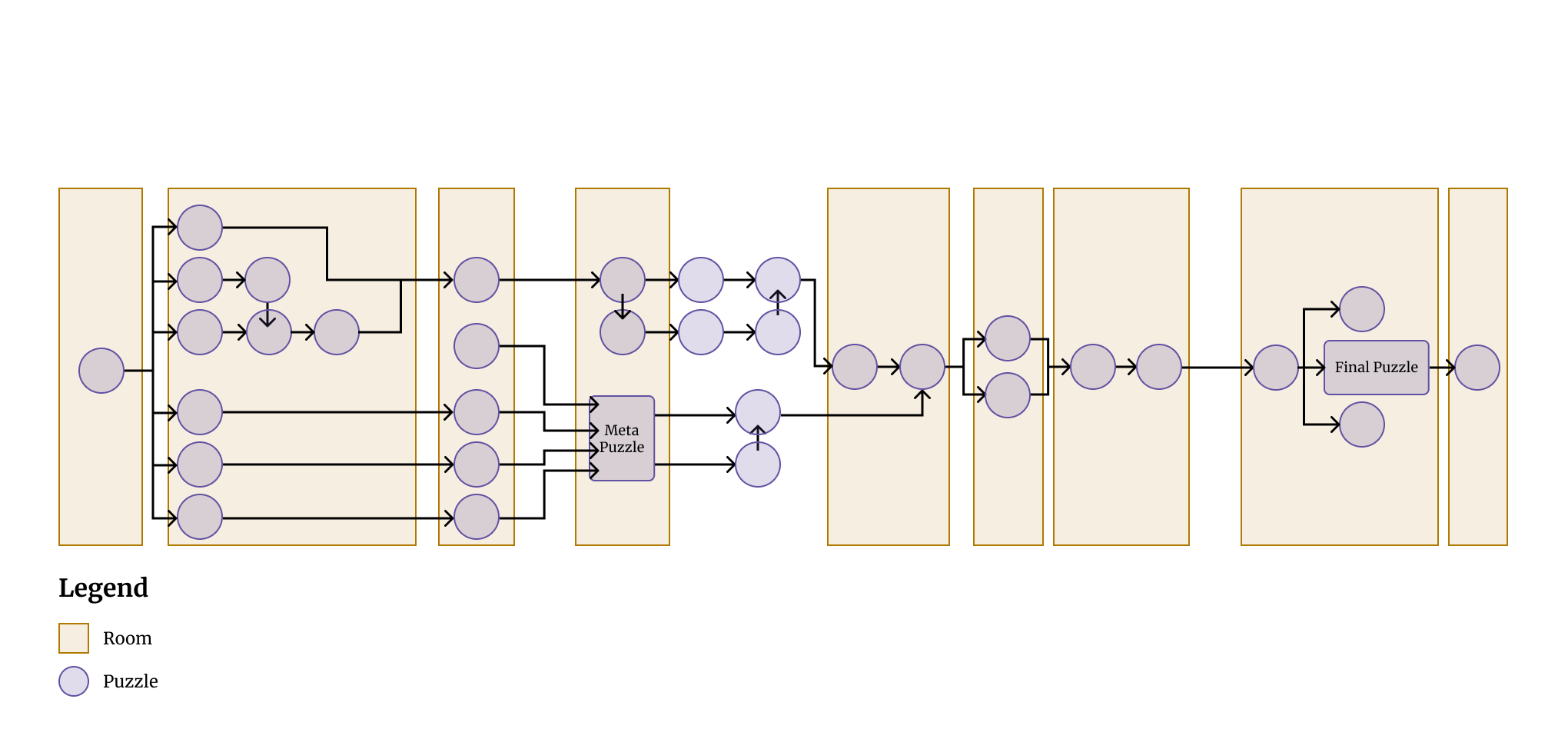

Sherlocked's upcoming escape game illustrates this reality very well. Throughout the experience players have one end-goal, to perform an occult ritual. The figure below shows a stylised representation of the (preliminary) puzzle flowchart through time. Their access to rooms (yellow boxes) is gradually rolled out. However, players are often asked to backtrack and the team is directed to work on multiple puzzles at the same time.

Another great example is Dark Park's The End, which I played with my colleagues at Sherlocked (and cannot recommend enough). Their game is mostly linear, leading from one room to the next. It hosts a room that is about traversal, getting from one place to another. Another, is more puzzle-y in nature. A few puzzles are available at the same time. This allows teams to divide the work, and all of them have to be finished to 'solve' that room.

Designers combine the previously defined approaches to balance out the pros and cons of each. Sometimes they might choose the experience of the individual over the team, and vice-versa. In other instances they might choose favour the progression of difficulty over the freedom of the players.

Linearity gaining traction

As part of the panel I hosted, Nick Moran spoke about escape games moving increasingly to linear experience. While that's not how he would prefer to design escape rooms, he thinks it's important to do (at least a little bit) what players want. Rather than having a task or puzzle for every player at any time.

Listen

The most praised games tend to be incredibly linear.

- Nick Moran (2021)

Puzzle Difficulty

Moran says linearity doesn't mean easier per se. But it does indicate a new found focus on story. It favours experiencing the narrative as a group, to connect with the emotional beats and keep the experience consistent across the group. Across the board, the people attending my panel said they aim to make escape rooms as accessible to mainstream players as they can.

Puzzle fairness

Like discussed in the literature review, puzzles should be fair and enjoyable (Bates, 1997;Elumir, 2018). What makes this especially true for escape rooms is that they are bound by a set time limit. Getting stuck hurts player experience in three ways:

- It frustrates players in that moment

- They start to distrust the game designer

- Wastes time, and lessens the time left (of an otherwise potentially good experience)

During both panels I heard several perspectives on the matter. They don't contradict, but all favour different parts of looking at the same issue.

Tommy conveys the primary thing to look out for are unclear goals. He suggests this is easily recognised when players start mindlessly throwing things to see what sticks. When that happens puzzles are usually unfair. This response is clearly backed by the theory of flow and especially group flow as well. Since Csikszentmihalyi states flow only occurs when goals are clear.

Furthermore, Nick Moran makes an interesting distinction regarding difficulty. He identifies three separate categories, and says only one of them should be implemented at the same time.

Listen

To talk about fairness. So I think there are three sides to difficulty. Which is physical difficulty, intellectual difficulty, and the difficulty of the unfamiliar. And I think you can only ever have a puzzle that tests people in one of three of these areas. And that's what I think helps construct a fair puzzle.

- Nick Moran (2021)

During the panel he explained what he exactly meant by that:

- Physical difficulty — performing a task that is actually difficult. Like throwing a ball in a hoop.

- Intellectual difficulty — the difficulty of understanding how something works.

- Difficulty of the unfamiliar — puzzles that break prior understanding of escape games.

Puzzles that have that last characteristic are simply difficult because they are new. When players have seen lots of escape room puzzles and understand how they work, they are no longer difficult.

Insight

Regardless of difficulty, escape room designers should create fair and enjoyable puzzles.

When the rules Moran get broken, puzzles are no longer considered fair or enjoyable.

Distributing difficulty

Theory has shown the importance of game flow, as discussed previously. Linear, story driven (video) games actively direct where players should look, and as a result influence how the player should feel during certain scenes.

These three examples show the variety (video) game designers have played with to craft a well-rounded experience. Carefully moderating challenge is essential to a good gameplay experience. Too much tension, and we wear out. Too much relaxation, and we grow bored. When the conditions previously described are met, experience seamlessly unfolds from moment to moment.

Escape room designers use different approaches to achieve the same result. Juliana Moreno Patel mentioned two techniques she uses to distribute difficulty throughout an escape game. On a meta level, both her and Ariel mention a bell curve.

Listen

When you're going into the bell curve of difficulty, having easy puzzles at the beginning really possible things gets your players to trust you. They say, okay, this is a game I'm going to be able to do.

- Ariel Rubin (2021)

They say they generally start easy, and raise difficulty around the middle of the game, where most players are around their optimal performance. Near the end they actually tend to limit difficulty again. Since most players won't be as sharp as when they started, and stress of the time limit starts to set in.

Regarding difficult puzzles, Juliana mentions that it's important to drip-feed players some tiny milestones, so they feel like they're making progress. Even if it's slow.

Listen

If they can be looking at this puzzle and at least figure out one small piece of it, where that really seems right, it's going to give them that rush and it's going to give them the desire to continue.

- Juliana Moreno Patel (2021)

Tommy Honton mentions that recent escape rooms have started adding more rooms. They use surprise often to make players disconnect from their previous challenge and environment. Those moments are distributed throughout the experience, which allows players to realise what effects their actions had on the world they interacted with.

Each room that opens up, you have a moment of disconnecting what opened up, and taking in that new data.

- Tommy Honton (2020)

Short moments to breathe allow players' focus to return, which readies them for the next challenge. They allow people to release tension momentarily, to be fully present for subsequent challenges.

Puzzle testing

To figure out whether puzzles are enjoyable, we have to connect with people in order to understand their needs. As Rita Orlov described, escape room designers should do play tests. Ariel Rubin was very clear about its importance as well:

Listen

The very, very best way to find [frustration] and to figure it out is through play testing.

- Ariel Rubin (2021)

I've experienced play testing a few times in practice, since Sherlocked is working on a new escape game (which I probably shouldn't have told you about 🤐). I've played the role of test subject, puzzle designer and documenting, although not all at the same time. Our first tests only considered one or two interactions at Sherlocked's office building, with colleagues who hadn't seen what we'd worked on.

Later we set up a test with people I didn't know, which we set up on-location at a new location in the Beurs van Berlage. We had set up about 5-6 interactions to test the tech and time players needed, but most of all on their ability to make players smile.

Since we had several subsequent tests in that last session, we were able to make some tiny adjustments in one day. Slowly improving the experience as we collected feedback. It also resulted in scrapping one of the puzzles I'd designed, which you have to be able to deal with as an escape room designer.

Iteration

Interestingly, running an escape room inherently means you're doing research on the experience you provide. Game hosts watch in on every game played, and instantly pick up when players disconnect from the experience. Escape rooms test almost like a restaurant improves its menu. They constantly receive passive and active feedback that can be implemented at every subsequent game, provided that knowledge is actually used.

Conclusion

Play testing has to be done early and often, and with players of varying abilities.

Conflicts of immersion

Escape rooms as a medium do well in some parts of immersion, but have much to improve in other areas. As Haley Cooper (2018) notes, the nature of escape rooms hinders the narrative immersion some other mediums do offer because spaces don't feel real. Furthermore, agency takes away control of pacing.

There have certainly been attempts resolve some of these issues, to make the three work better together. At Sherlocked they use several techniques to blur the lines between reality and fiction. These exist elsewhere in the industry, but they are certainly not employed in every experience.

Blurring when the experience starts

One of the things Sherlocked's The Vault is praised for is its ability to slowly slip teams into the experience. You'll get some cryptic text messages, and slowly but surely you're rolling into an immersive adventure. There is no host to welcome you. Instead, you'll have to word-wrestle your way into a high-class art gallery. You never stop to think 'oh now we're really getting started'. That is something Victor thinks Sherlocked does best.

One of their primary goals designing new experiences is to have you guessing whether what just happened is real. An excellent anecdote of them succeeding at that is the story Victor told me about team from Saudi Arabia that didn't want to continue playing The Vault. They genuinely believed to be participating in an actual heist. While not every player responds as strongly, at least some people have been second-guessing.

The solution depends on the story

Another area of focus is using puzzles as a touchpoint for the narrative. One technique is to make the challenge and story co-depend on each other. In order to progress through the escape room, players have to know the story, like Nicholson (2016) suggests. Victor, notes that it's important to make this clear from the start, to set a precedent for late-game puzzles.

The trick is to make it clear from the start that you can’t achieve the one without the other. That in order to complete the game, you need to understand the story.

- Victor van Doorn

This hook is used to draw even the most puzzle-savvy players into the narrative.

Use of historical figures and places

The last point Sherlocked uses is that their narrative is heavily inspired by real historical characters. Borrowing names like Tesla and Newton instantly link the narrative to the real world. They employ historical figures as a basis for the narrative. In a similar vein, they use real places for their sets. They are built within the confines of a monumental building. The Vault, for example, is built within the vault room at Beurs van Berlage, which instantly grants their story some credibility. Their experiences borrow characteristics from docudrama feature films (eg. Bohemian Rhapsody) along with science fiction (eg. Star Wars). Thus ultimately falling somewhere in between.

Conclusion

Using real world characters, buildings and environments, the lines between fiction and reality can be blurred. These techniques make narrative, sensory and challenge-based immersion with, instead of against each other.

How does the experience of enthusiasts differ from other players?

This section explores what an enthusiast expects from an escape room, that mainstream players do not.

Personal flow zones

Most escape room enthusiasts, those that have played lots of games before, have more skill than the typical novice player. Like Chen (2007) described, this is typically solved by offering the player some kind of choice. Jesse Schell (2019) notes there is much debate about the difficulty of video games as well. Whether it is a good thing or a bad thing to allow players to reach a level of frustration zone that some give up on the game depends on who you ask. But at least some escape room designers seem to be open to the idea. Tommy Honton said this:

Listen

I don't mind crunching at something difficulty wise, both as a designer and hoping people enjoy that same thing, and also as a player. Provided it is satisfying and fair. [T]hat's I think the big balancing act, making something fair.

- Tommy Honton (2021)

Within the realm of video games, there is one genre-defining game, holding cult-like status; Dark Souls by FromSoftware (Vaatividya, 2020; The Act Man, 2018). Dark Souls games (there are sequels) are celebrated partially due to their world-building, but are generally spoken about as the most challenging games in the business. What Dark Souls does well though is to be fair, and players care about progressing through the world. They care about it enough to learn about their opponents while playing Dark Souls.

Dark Souls players expect to die multiple times to overcome an enemy. But they know they return with a little nugget of information about their attacks. While most players will get frustrated at a game like this, Dark Souls has also accrued a solid fanbase, since some players desire such an experience. Another example of teaching the player how to play is The Witness, as designed by Jonathan Blow.

The language of puzzles

Mark Brown (2016) explains how Jonathan Blow, designs puzzles. His approach has several impactful results on the result. His puzzles constantly build on each other and teach the player how to play. The Witness slowly increases difficulty, because difficult puzzles can only be passed when players understand how easier puzzles work first. His design philosophy is as follows:

Mechanic

Jonathan Blow starts with a game mechanic. In The Witness everything is built around mazes.

Rules

He then actually build the puzzle. By playing with these basic puzzles, rules emerge. In The Witness, you have to separate colours.

Consequences

By building these rules, new consequences arise. In The Witness that might be blocking the most obvious exit.

Mechanic

Every puzzle illustrates a consequence you have to internalise. In The Witness you have to realise you're blocking that primary exit by offering an alternative exit.

These puzzles were designed by playing with them like a player would. They naturally evolved as part of slowly adding more rules.

There's an extent to which this game designed itself.

- Jonathan Blow (2016)

By adding constraints, the puzzles have a natural progression to them. The result is that players can start to understand the 'language' of these puzzles. They will learn how the designer created these puzzles, because they follow the designers' footsteps.

Insight

Video gamers enjoy difficulty when it is presented in the right way.

Escape rooms that want to use dynamic difficulty could use a similar idea to teach players how to play their escape room. Players that quickly pick up the language of the puzzles presented could skip a few that others need to fully grasp what they're being taught.

Speaking with enthusiasts

The industry of escape rooms is a bit strange, in that most escape room designers are also their biggest enthusiasts. I've gained a lot knowledge through speaking with industry figureheads, but wanted to learn from enthusiasts with another profession as well. I spoke with three enthusiasts who all had different wishes regarding difficulty. Though most have shown a distrust against difficulty.

Enthusiast 1

The first said she tends to shy away from an expert mode if she would get to choose between multiple levels of difficulty. She said these experiences often feel difficult through omission. They hide so much information that she had to guess what the designer had in mind. It's obvious she doesn't trust designers to make proper difficult challenges. Her favourite experiences however, was The Cooper Case, one I played myself as well. She specifically enjoyed that it's focused around puzzles while maintaining a theme. It also shows clearly that preferences vary wildly, and that there is a need for escape rooms like these, since I did not enjoy The Cooper Case at all. Remarkably enough, she also mentioned something I would have expected to hear from experts, rather than players. According to her, linear rooms work perfectly for smaller groups, but with any more than four in a team, players start to wander, since there isn't enough happening for everyone.

Enthusiast 2

The second enthusiast said something particularly interesting about hints. She said she'd much rather escape with hints, than being stuck. While before she only wanted hints on her own accord, recently she's been more trusting of the game masters' ability to moderate the speed players progress at. She did express strong feelings against automated hint systems.

Automated hint systems, those make my [REDACTED] go limp.

- Enthusiast 2

Those are often used to run multiple escape rooms at the same time. She thinks that is unfair to a paying customer, considering how expensive escape rooms sometimes are.

Enthusiast 3

The third enthusiast I spoke with was mostly interested in the tech behind the room. As an enthusiast, that has often played multiple rooms of the same business, he expects to get a behind-the-scenes look. Another thing he would really like is a way to reflect on his team performance.

This is something I want; the ability to reflect on our team performance. To determine where we miscommunicated.

- Enthusiast 3

Contrary to enthusiast 1, he enjoyed linear experiences, regardless of group size. To him, it's much more important to experience the escape room as a group, than to have something to do at all times.

Through the experience of talking with these enthusiasts I learned that even speaking with just three top escapers, the expectations of what an escape room should be, vary wildly. Overall my conclusion would be that:

Insight

Enthusiasts are not fundamentally against harder difficulty, but the industry has to gain the trust of players by making hard difficulty games that are fair.

How might we alter escape games based on players?

Now, dynamic difficulty isn't exactly a new idea. There are several examples of dynamic difficulty to be found, across several mediums. In the video gaming industry there are the obvious solutions like matchmaking (opponents are matched on experience level). And escape rooms have used less obvious ones as well. I've spoken with several escape game designers and hosts, and analysed video games. With the purpose of revealing some of the mysteries of dynamic game design in its current state, which we'll discuss in this section.

Video games

The lowest hanging fruit is looking at video games. They are easy to find examples of (and fun to play as part of research). Video games get reviewed and analysed a lot, and have become an important part of pop culture (Wolf, 2017).

The majority of games actually don't incorporate dynamic difficulty at all. Instead, they give the player the option to choose a difficulty level. The big difference between video games and escape rooms is that the former are easy to replay. Players can choose to play at a lower difficulty first, and replay at a higher one later. Opposed to that, to replay escape rooms, players have to pay money and assemble a team again. In that regard, it's more important to get challenge right the first time.

Consistency

Tommy Honton explained he sees the value in dynamic difficulty, but cares about the consistency of his experiences as well. He sees that as the main hurdle to overcome.

Listen

The challenge for me is the idea of consistency. I want something that I make to be consistently good and enjoyable for novices and for experienced players.

- Tommy Honton (2021)

The problem being that players, whatever their experience, wouldn't be able to discuss their experience with friends if they are wildly different.

Insight

Game designers want to create consistent experiences, so players of any level can talk about their experience without major disconnects.

In that sense escape rooms borrow the worst qualities of video games and movies. Many video games, especially open-world, invite players to play how they want to play. The difference is that video games are a fairly easy medium to return to. Playing an entire game or a specific section are something players do on the regular. Movies on the contrary, are a linear experience. They are harder to return to, but they are exactly the same for everyone that watches them. Save for the viewers' own interpretation and genre preferences.

Opaque adaptation

Another important issue raised, is the need for ownership. Self-determination theory determined, people have the need to feel competent. People want to feel smart as they solve an escape room, to feel smarter than they thought they were. When they obviously change based on the player we ruin that feeling. No longer will players feel like they were smart, they might even feel the exact opposite. Like enthusiast 2, Tommy Honton feels like mis-timed or overt hints are jarring to the experience, and break immersion. He thinks hints that subtly direct players may solve some of those problems:

Listen

[B]eing able to, you know, solve some of those problems with the idea that a light glows and I look over, and I noticed the light and I don't connect the fact that I'm being hinted at.

-Tommy Honton (2021)

Resident Evil 4 has hidden its adaptive nature incredibly well too, says Mark Brown (Game Maker's Toolkit, 2015). He adds the quality to hide this from players has another major benefit. When systems like these are unnoticeable players can't trick it. If players are aware that difficulty adapts to their performance, they might use it to cheat the game by making mistakes first, and picking up later. These ideas boil down to a single requirement.

Insight

Adaptive difficulty, including changes to game flow and being hinted at, should be imperceptible.

Eyal Danon believes the way we control escape rooms with software plays a big part in resolving these issues.

Escape Room Software

Escape rooms have become more and more reliant on technology. Integrating lighting, audio, moving items, projections and many other forms of interactive media. Primarily they form the basis for sensory immersion, but they have been used to build out other types of immersion as well. There are quite a few competitors in the space, though asking the Escape Room Start Ups Facebook group has shown some prolific support for Cogs, developed in part by Eyal Danon.

I've had the pleasure to speak with Eyal, who is an ex-escape room designer turned tech entrepreneur. Cogs runs interactive experience such as escape rooms, immersive theatre and experiential marketing. Technically speaking, Cogs isn't just a piece of software though. They provide a suite of hardware to connect lights, music, projectors and bespoke puzzles as well. Essentially, it's a platform to make the design and implementation of interactive experiences as accessible as possible. Eyal has seen two different approaches:

Listen

We've seen people do the most boring version, which is "it's 40 minutes and they still haven't got this open this cupboard, give them an easy clue". Which is very unsatisfying for the players. But we've also seen people do it in a much more elegant way.

- Eyal Danon (2021)

The more interesting approach, according to him is:

Listen

Instead they kind of shift every single puzzle, just gets slightly easier or slightly harder, but it still fits well within the narrative. Or they just go "actually, we're going to give you a little bit more narrative in this direction".

- Eyal Danon (2021)

Metrics

If we consider the solution to dynamic difficulty as a system with inputs and outputs. We have to define metrics that will indicate whether a group is currently experiencing the right level of difficulty.

During the panel I explained that I suspect team communication could be a good indicator for flow, or challenge-based immersion. My statement was based on a triplet of theories:

- Jesse Schell's observation that multiplayer video game players experiencing flow often communicate enthusiastically with each other

- Keith Sawyer's conditions for group flow

- Marlow's meta-analysis of team communication showing clear indicators for team familiarity

Ariel Rubin said she thought I was on the right track, but that engagement and frustration are the best indicators to look at.

Listen

Engagement is really the thing. Because I think consistently what you'll see is, as people get frustrated, they start fussing with things or they just sit down for awhile. It's it's how engaged are they in continuing to solve? And how many mistakes they make.

- Ariel Rubin (2021)

Ariel also mentioned groups make mistakes more often when they are disengaged. When players disengage they usually start brute forcing puzzles, and lose interest in learning how they should solve the puzzle. Brute forcing also suggests that groups like these are no longer intrinsically motivated to play the game. At that point they solely play to progress the story, or to escape. Players who get frustrated are affected by the overjustification effect, it seems.

Eyal had a different answer to the same question. Like Tommy said about clear goals, it's important that teams keep moving forward. He generally suggests escape rooms use momentum as an indicator for enjoyment. By which he means they pick up pace as they play, increasingly solving more and more puzzles in the same time. It doesn't matter whether a group is faster or slower than the one before, but the overall momentum of the group should go up right near the end. Essentially, they play against their own previous performance.

Listen

[T]he thing that we look at more than time is momentum. So you are designing some, a particular momentum. You want them to pick up whether they're a slow team while they're fasting, they're still picking up and then they slow down when they're towards the end.

- Eyal Danon (2021)

Eyal says he's also tried to use sentiment analysis, inferring how players feel based on language, as an input for Cogs as well. However, he says the technical implementation of a system like this is problematic in practice.

Listen

We've done a little bit of work with sentiment analysis with the Cogs system. [...] Which we then shelved entirely.

- Eyal Danon (2021)

Between groups not be speaking a lot as part of cultural differences, or groups speaking different languages entirely and every room being different, it's hard to get enough sample data. If you know anything about machine learning, you'll know that's exactly what's required to create a really good machine learning model.

Beyond some specific input types I've also spoken with a few designers of dynamic difficulty in escape rooms (or similar).

Full systems in the wild

Push the Button

I also spoke with David Middleton, Co-founder of the UK based Bewilder Boffs Studios, who offer design services for escape room startups. They have created their own series of escape rooms under the Bewilder Box brand as well.

At the time of speaking, David was working on a mobile escape game, which fits inside a box. It features a specific set of constraints, to maximise the time played within a 30 minute time limit.

Their solution involves a self-resetting box, that offers clues on a set rhythm. The host-less experience is broken up in 5 puzzle sections. Each puzzle drip-feeds clues through icons, and practically spells out the solution after 5 minutes have passed. Because of that players of any experience get the rush of almost (not) finishing the game.

The idea is to get everyone in that James Bond phase of the game

- David Middleton (2020)

The Gallery

One of the first people I spoke to for this project is Niels Jonker (2020) from Escapist, another escape room business in Amsterdam. Niels Jonker has designed The Gallery, another escape room featuring dynamic difficulty. He actually said it's quite easy to do, and like David, he tries to get every group to escape at around 58 minutes, which he said is to maximise 'value for money'. Niels made three particularly interesting points:

- The Gallery was initially a 'normal' escape room, but dynamic difficulty was later added since the record was set at 36 minutes, which he thought was too short for a 60 minute experience

- Result of supporting large variations in group sizes. Groups of two people are inherently less fast than those with more people playing at the same time.

- He only starts adjusting puzzles in the second half of the game. Early on the game it's really hard get a grasp on the team's speed.

- In total The Gallery has three adjustable puzzles. All puzzles are set on a timeline, when players run in on the timeline they get an extra or more difficult version of puzzles.

- One of the puzzles is hidden. When a team is very quick they add an extra puzzle that becomes visible with blacklight.

- The second puzzle either tells you exactly what to do, or is like a game of mastermind (with two difficulty levels).

- The final puzzle moderates through physical difficulty. Imagine playing a game of Operation, but the holes are larger or smaller.

Lab13

Jesse van der Lely, from Live Escape, designed and hosts a room in Rotterdam called Lab13. Their system is completely opaque, and players never notice it, Jesse says. Their approach is that they start with a base game. They never remove any puzzles from the base game, but they do give faster teams (one or) a few extra puzzles, as determined by a big flow-diagram of switches. He mentions their base game has an issue, it's too hard for most players. Their shortest version is too ambitious for most teams to finish, let alone the game including all extra puzzles. Another caveat that adds to this problem is that their current implementation doesn't allow for puzzles to become easier.

When you show a clue to a difficult puzzle, you can't go back when they get stuck.

- Jesse van der Lely (translated from Dutch) (2020)

Furthermore, Jesse mentions their room has parallel puzzle tracks. They use this to their advantage by determining which puzzles are being solved first and fastest. If a team solves a logic puzzle really well they get more of those, if they do much better at a maths puzzle, that's what they get instead. Though the extra puzzles never build on story in a big way, to ensure a consistent experience across players. What Jesse is doing with Lab13 sounds like a rudimentary approach to incorporate Nicole Lazarro's theory of catering to preferences. To offer not only different levels of difficulty, but also cater to different preferences regarding puzzle types.

Conclusions / Key Insights

Escape room designers have to choose what they aim to do with dynamic difficulty. Some only desire to maximise the time each team gets to play their experience. While others might want to give everyone the rush of "almost not escaping". In both those cases we are dynamically controlling time and experience.

Insight

Difficulty is currently determined by duration, this may be the wrong metric.

To me, escape rooms are special in three ways compared to other forms of entertainment:

They occur in a physical space

Sensory immersion comes easy as a result of:

- Multi-channel information

- Completeness of information

They are a group experience

The experience has to work for multiple people, at the same time. The experience has to work for varying group sizes.

There is a time constraint

Escape rooms promise an experience of x minutes. We better deliver.

Now, these points might seem obvious, especially to avid escape room designers. But it took a while before they really sunk in for me. In the next chapter I will propose recommendations to consider when developing a dynamic difficulty system.